This article seeks to examine the price and affordability of water and electricity in South Africa. We embark on a tough but important journey to shed light on how the price of electricity and water has changed over the last 25 years, and how these basic needs have become less affordable for us, the citizens of South Africa.

On this journey, we discuss the following topics in 5 short chapters (click the link to go directly to a specific chapter):

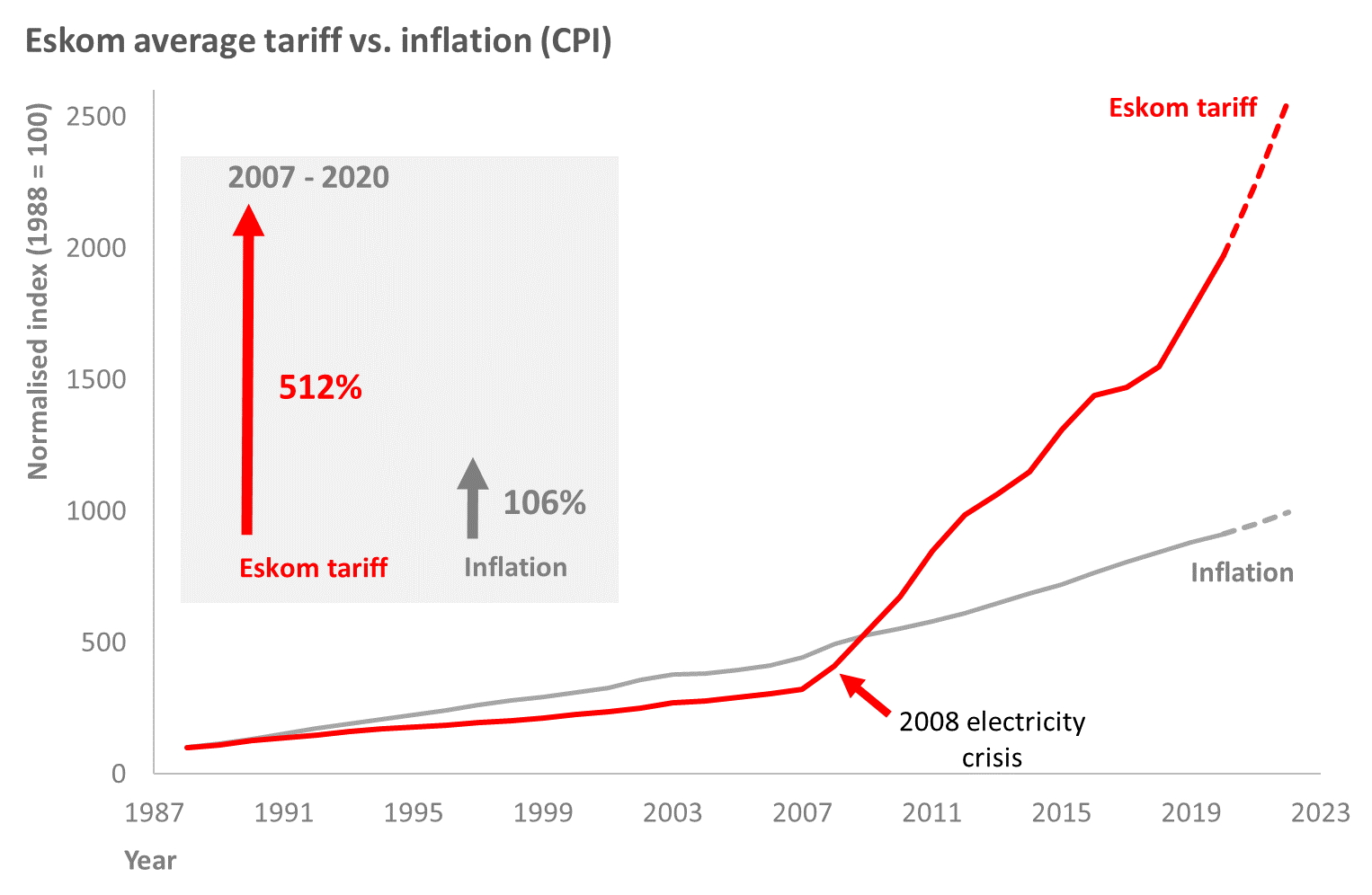

The increase in Eskom’s average electricity tariff vs. inflation (CPI) – click here to read

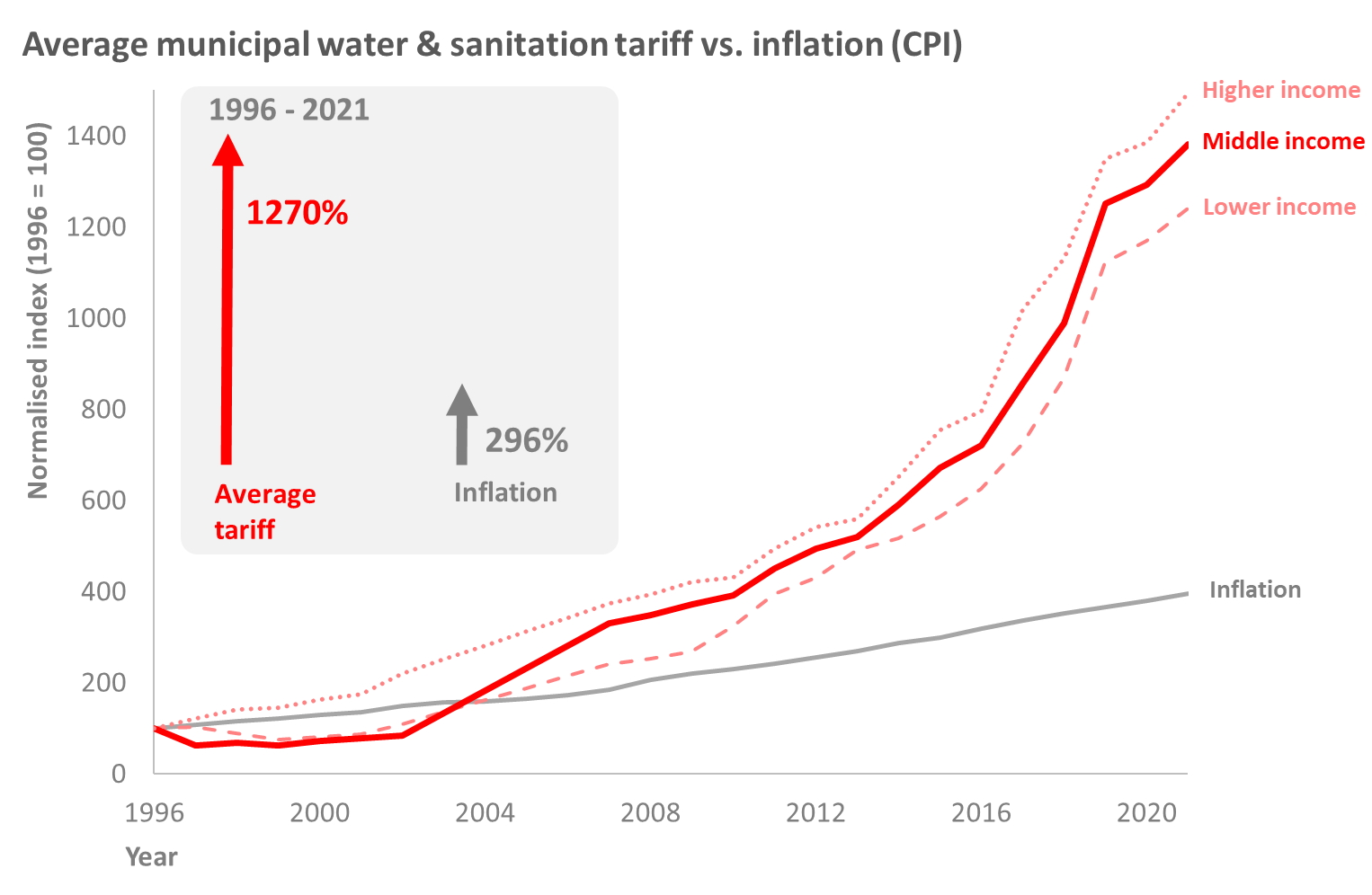

The increase in the average municipal water and sanitation tariff for three different income levels vs. inflation (CPI) – click here to read

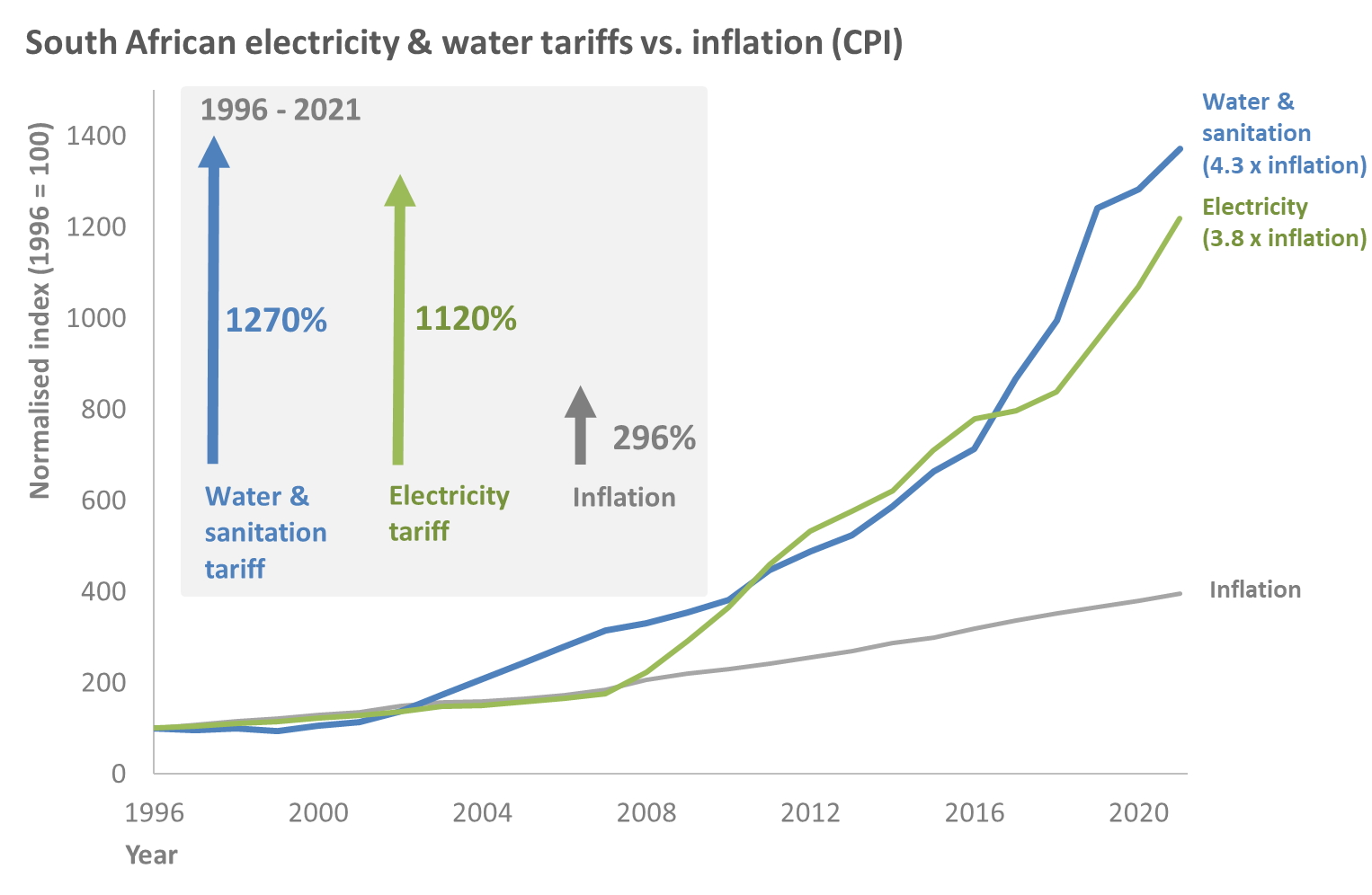

The contrast between the increases in South African electricity and water tariffs vs. inflation (CPI) – click here to read

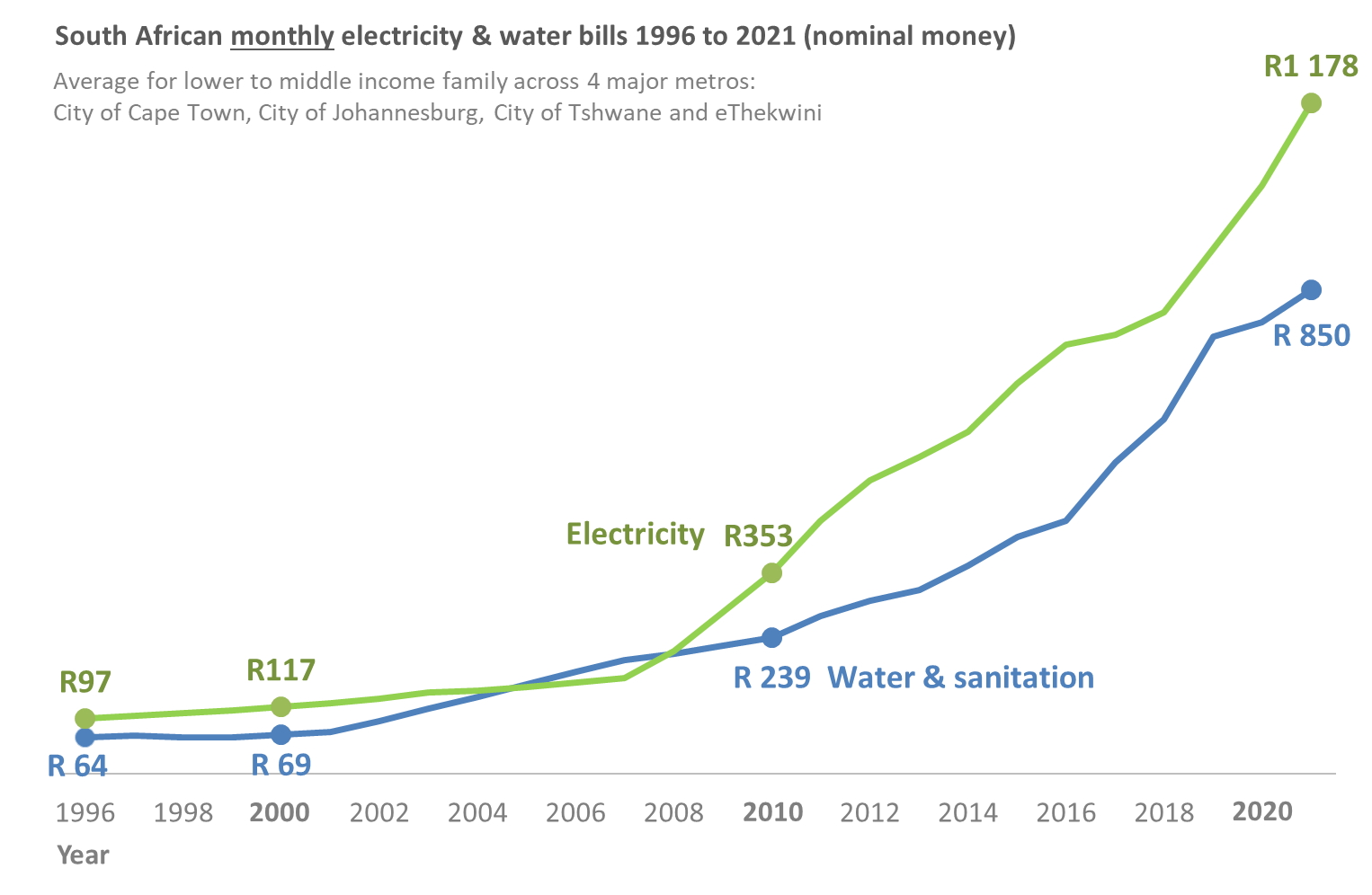

How South Africans’ monthly electricity and water bills have changed in the past 25 years in both nominal and current money – click here to read

The combined electricity and water bill of an average South African household vs. average household disposable income in South Africa – click here to read

Each of the above topics is accompanied by a graph to aid the discussion and illustrate the seriousness of the situation in South Africa.

We hope to highlight the pertinence of wise water usage and efficient energy consumption and to stimulate the conversation surrounding what we could and should do to ensure sustainable and affordable access to these basic needs for all South African citizens.

For methods, assumptions and references, click here.

The state of South Africa’s electricity provider, Eskom, is no secret. Plagued by ageing infrastructure, mismanagement, corruption, shrinking or stagnant revenues and increasing debt, the state-owned utility is caught in what is known as a ‘death spiral’.

The impact of these issues manifests in two ways. The first is known as load-shedding, something with which we as South Africans have become all too familiar. The second is the infamous Eskom electricity tariff increases. Ideally these tariff increases would be somewhat in line with increases in inflation… Oh what a perfect world that would be!

In sunny South Africa, electricity tariffs have increased by 512% from 2007 to 2020 (see the graph). That is 5 times faster than inflation! Eishkom?

To top it all off, Eskom was recently granted a R13 billion clawback by NERSA, as well as an additional R69 billion clawback, resulting from a court judgement in Eskom’s favour[a].

What does that mean for us? We, the citizens of South Africa, are set to experience further rapid electricity bill escalations over the next few years. It goes without saying that those increases will not be accompanied by improved service delivery.

Speaking of rapid escalations, has anyone kept an eye on their water bill? In the next chapter we take a closer look at municipal water tariffs.

In the previous chapter we discussed the 512% increase in the average Eskom electricity tariff since 2007. We shall now embark on the 2nd leg of our journey in which we highlight an equally odious development in a tariff that has received a lot less negative press: Water and sanitation.

You are not alone if you allowed the increasing cost of your most basic need to go unnoticed…

Perhaps now is the time to explore the real water tariff trends, overshadowed by Eskom’s conspicuous plight and camouflaged by a complicated tariff structure, but which impacts our daily lives as South African citizens. Think back to ‘Day Zero’ in 2018 and the questions surrounding a lack of access to water and water insecurity in South Africa.

Now ask yourself this: Is it possible that the cost of the water provided by municipalities has increased faster than inflation, considering the deteriorating service delivery on a broader scale?

As can be seen in the graph, average municipal water tariffs have increased four times faster than inflation since 1996.

Essentially, the average municipal water tariff was almost 1300% higher in 2020 than in 1996… Unfortunately, we must bear this burden together with that of Eskom’s runaway tariffs.

In the next chapter, we compare electricity and water & sanitation tariffs over the past 25 years and consider why the increases in average municipal water tariffs have gone largely unnoticed.

In the previous chapter, we highlighted the dizzying increases in average municipal water tariffs since 1996. The numbers are startling to say the least, which begs us to ask: how could such exorbitant increases happen right under our noses without a public outcry?

The bulk of negative public attention and sentiment has been aimed at Eskom… Rightfully so, however, it may have distracted us from an equally pressing issue.

Water tariffs (1270%) have increased even faster than electricity tariffs (1120%) over the past 25 years (1996 to 2020).

But we have an excuse for our ignorance, for these staggering municipal water tariff increases are cloaked by more than Eskom’s shadow.

To begin with, our water tariffs appear as only one component in a larger municipal bill and are thus hidden in the details. Furthermore, every municipality sets its own water tariffs and structures them in a more complicated way than residential electricity tariffs. This tariff structure is known as block tariffs, where the price per unit of water increases in blocks as usage increases.

Consequently, it is more difficult for people to make direct comparisons and to know the real cost of each unit of water.

Our journey to unearth the truth would be incomplete without investigating the real monetary impact of these increases. How has the price of water and electricity changed over the past 25 years in current money terms? In the next chapter, we illustrate and discuss how these increases have affected our monthly electricity and water bills in both nominal and current money.

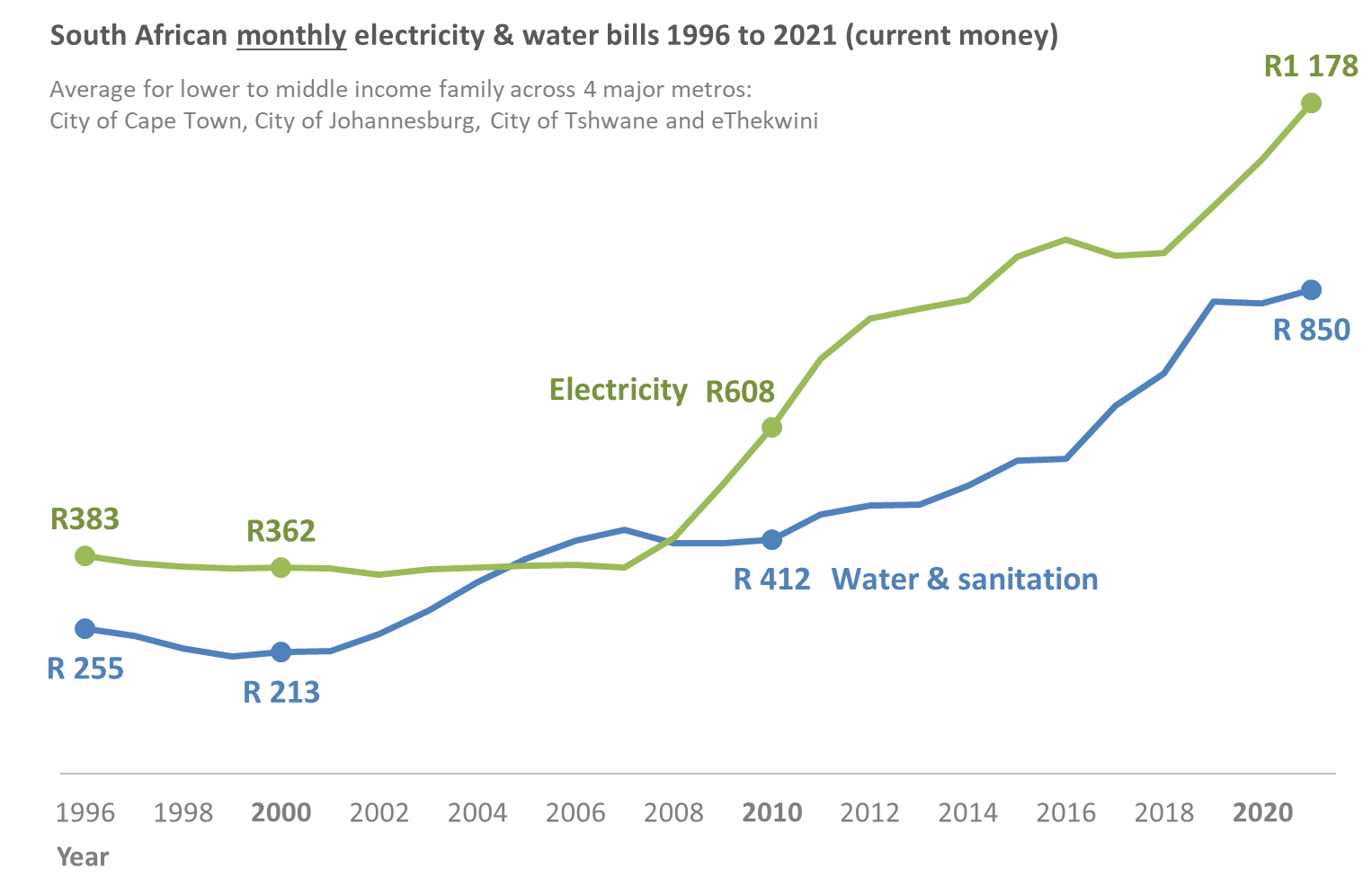

Electricity and water tariff trends in South Africa were explored in the previous articles in this series. But this would be rather meaningless without highlighting how this translates into the monthly electricity and water bills of the average South African.

What was the monthly water and electricity bill 25 years ago compared to what we are paying today?

Not accounting for inflation, the average monthly electricity and water bill for lower to middle income families was a mere total of R161 in 1996. Fast forward to 2020 and this average monthly electricity and water bill has ballooned to R2 028!

The question you should now be asking is: “how much of that increase was due to inflation”?

As I am sure you would have guessed, the answer is not much. The next graph tells the story.

Essentially, this graph tells us that in 1996 the average electricity and water bill was R638 in today’s money. A stark contrast to the R2 028 average monthly electricity and water bill in 2020.

These prices have been adjusted for inflation and so the increases seen in the above graph are entirely the result of above-inflation tariff increases implemented by Eskom and local municipalities.

An over-arching question remains: Can we afford these exponential increases in the cost of two of our most basic needs?

We will answer this important question in the final leg of our journey, in which we compare the average electricity and water bills to the average household disposable income in South Africa over the past 25 years.

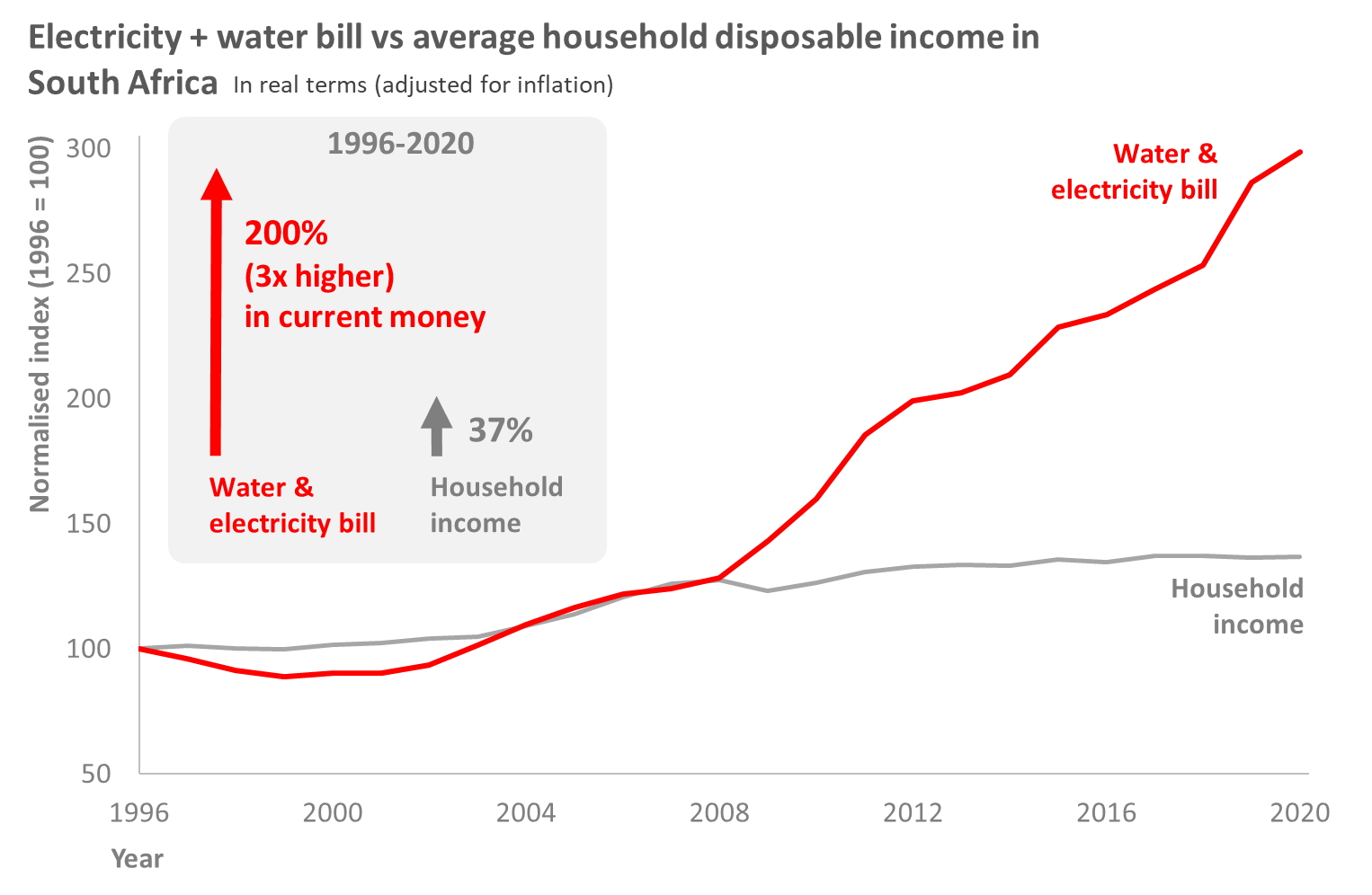

The final leg of our journey is arguably the most pertinent. We know for certain that inflation is not the major cause of the increases in electricity and water tariffs. But the real question is: Can we afford these spiralling electricity and water bills? Did South Africans’ average income keep pace?

Looking at the above graph, the conclusion must be a deafening no. While our average monthly electricity and water bills have increased by 200% since 1996, our average household disposable income[b] has increased by a mere 37% since 1996.

The divergence between these basic costs and household income is especially pronounced from 2008 onward (the past 12 years). Furthermore, our disposable income has been impacted by economic downturns and, more recently, rising income tax rates.

Two of our basic needs have become increasingly unaffordable and we continue to struggle with load-shedding. Now more than ever, we need to take practical steps to explore alternative solutions.

Although the current outlook is bleak, there is hope on the horizon. In October 2020, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy gazetted amendments to the electricity regulations, allowing municipalities to generate and procure their own electricity. South Africa has some of the best solar PV and wind resources in the world and the cost of these options continues to fall, making self-generation as well as the renewable aspirations of the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) more viable every day.

Average electricity consumption data for different LSM (Living Standards Measure) categories was obtained from Reference [1]. LSM 1 to 4 were classified as low income, LSM 5-6 were classified as lower to middle income and LSM 7-10 were classified as middle to upper income.

Average water consumption data for low, middle & high income households was obtained from References [2] and [3]. It was assumed that water consumption remained constant over time, although it is possible that it has reduced somewhat over the years due to increasing prices and water restrictions. However, the data in the references used ranged from 2004 to 2015 and water consumption was relatively constant over this period.

Eskom electricity tariff data were obtained from its website [4].

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) was used as inflation measure. CPI data was obtained from References [5], [6] and [7].

Municipal electricity and water & sanitation tariff data for the four metropolitan municipalities Cape Town, Johannesburg, Tshwane and eThekwini were obtained from their respective websites [8], [9], [10] and [11], as well as third-party reports [12].

Where water restrictions were in place and water restriction levels changed during the course of a municipal year (such as in Tshwane or Cape Town), the tariffs for the water restriction level that was in place for most of the year was used to calculate the average tariffs for the different income levels.

Tariffs for all income group were calculated based on the ‘single dwelling houses’ category and not for apartment buildings.

‘Indigent’ tariffs were not applied in calculation of the average tariffs for the lower income group (in other words, this group is not representative of the ‘lowest’ income group, but rather the ‘lower’ income group).

All tariffs are VAT inclusive.

All tariffs are metered tariffs (as opposed to prepaid tariffs). However, for most municipalities and in most years metered & prepaid tariffs are structured the same.

For the period 1996 to 2002, the water tariff data obtained excluded sanitation tariffs. The sanitation tariffs for this period for each of the four metro municipalities (Cape Town, Johannesburg, Tshwane and eThekwini) were estimated using the respective municipality’s average sanitation tariff as % of total water & sanitation tariff for later years for which full data was available.

Disposable income data was obtained from Reference [13].

No water & sanitation tariff data could be obtained for the four-year period 2003 to 2006. For this period, linear interpolation was done between the 2002 and 2007 tariffs for each municipality.

Average tariffs across the four metro municipalities in the study (Cape Town, Johannesburg, Tshwane and eThekwini) were calculated as simple averages (in other words, not weighted by measures such as population size).

[a] https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/eskom-says-it-needs-r23bn-more-from-tariffs-in-2021-to-remain-a-going-concern-2020-11-05

[b] ‘Disposable income’ is defined as the total income after tax (in other words before expenses), not income after expenses.

[1]. Goliger, A. and Cassim, A. (14 and 15 July 2017). Tipping Points: The Impacts of Rising Electricity Tariffs on Households and Household Electricity Demand. 3rd Annual Competition and Economic Regulation (ACER) 2017 Conference, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Website: http://www.competition.org.za/s/Parallel-3B_Goliger-and-Cassim_National-Treasury.pdf. Last accessed: 2017/08/21.

[2]. Viljoen N. 2015. City of Cape Town Residential Water Consumption Trend Analysis 2014/2015. Website: https://greencape.co.za/assets/Sector-files/water/Water-conservation-and-demand-management-WCDM/Viljoen-City-of-Cape-Town-residential-water-consumption-trend-analysis-2014-15-2016.pdf. Last accessed: 2020/08/02.

[3]. Bailey WR, Buckley CA. 2004. Modelling Domestic Water Tariffs. Proceedings of the 2004 Water Institute of Southern Africa (WISA) Biennial Conference. Cape Town, South Africa, 2-6 May 2004. Website: https://wisa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/WISA2004-P004.pdf. Last accessed 2020/08/02.

[4]. Eskom Tariff History. Website: http://www.eskom.co.za/CustomerCare/TariffsAndCharges/Pages/Tariff_History.aspx. Last accessed: 2020/08/04.

[5]. Focus Economics. Inflation in South Africa. Website: https://www.focus-economics.com/country-indicator/south-africa/inflation. Last accessed: 2020/08/04.

[6]. Bureau for Economic Research. Inflation Expectations. Website: https://www.ber.ac.za/BER%20Documents/Inflation-Expectations/?doctypeid=1065. Last accessed: 2020/08/04.

[7]. Statistics South Africa. CPI headline inflation history. Website: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0141/CPIHistory.pdf?. Last accessed: 2020/08/04.

[8]. City of Cape Town Tariffs. Web pages:

https://resource.capetown.gov.za/cityassets/Files/Tariff_increases_from1July17.pdf

[9]. City of Johannesburg Tariffs. Web pages:

https://www.joburg.org.za/services_/tariffs/Documents/annexure%2020.pdf

https://www.joburg.org.za/Campaigns/Documents/2014%20Documents/2014-15%20approved%20tariffs.pdf

https://www.joburg.org.za/services_/tariffs/Documents/2015-16%20tariffs%20for%20approval.pdf

https://www.joburg.org.za/documents_/Documents/Other/traffifs/Approved%20tarrifs.compressed.pdf

https://www.joburg.org.za/documents_/Pages/Key%20Documents/other/links/tariffs/Tariffs.aspx

[10]. City of Tshwane Tariffs. Web pages:

http://www.tshwane.gov.za/sites/Departments/Financial-Services/Financial-Documents/Pages/Promulgated-Tariffs.aspx

[11]. eThekwini Tariffs. Web pages:

http://www.durban.gov.za/Resource_Centre/Services_Tariffs/Water%20Tariffs/Forms/AllItems.aspx

http://www.durban.gov.za/City_Services/electricity/Tariffs/Pages/default.aspx

[12]. Third-party websites used as sources for municipal electricity, water & sanitation data:

https://greenaudits.co.za/2016/10/20/high-water-restriction-prices-for-cape-town-dec-2016/

http://www.rrva.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/New-Tariffs-and-Rates-for-CoJ-2011-12.pdf

[13]. South African Reserve Bank data. Website links: